Exposed as they are

to road hazards and the elements, few license plates are found in

perfect condition. This being the case, collectors and others are often

inclined to try their hands at restoring plates to their original

condition. Any person contemplating such an endeavor, though, should

understand from the outset that an accurate and quality restoration is a

difficult task which requires a great deal of knowledge, skill and

patience.

But should a plate even be restored at all?

Generally speaking, a rare or valuable plate that has any significant

amount of its original paint on it should not be restored or even

“touched up.” Doing so will only reduce its value and aesthetic

appeal to a fraction of what it would have been if left alone. A purist

will say that rare or valuable plates that have any residual original

paint at all should be left entirely as-is. Even washing a plate with

plain water can ruin the original paint. Think long and hard, do your

research and ask knowledgeable collectors before starting any

restoration.

Once the decision is made to restore a plate,

ask yourself if you have the aptitude to do so and the willingness to

follow through to completion. For starters, one must have mastered the

art of sheet metal work so as to be able to repair dents, bends, rust,

pits, holes and other injuries to a level of perfection that the metal

is as flat and smooth as the day the tag came out of the stamping press.

Then there is the matter of painting the plate.

But before one even starts to paint, and

indeed, before the paint is even bought, the would-be restorer must

meticulously research what the correct colors are for plates of the same

type and year. It is a common error that people attempting restorations

look at a plate of another type and assume that all plates for that

particular year are the same colors. It is often the case that they are

not, and lack of attention to this detail results in wasted time, effort

and money, not to mention a plate that looks nothing like it should.

Only when these details are attended to should painting begin.

Spraying on the background color is a skill

that can be mastered with a modicum of practice, but coloring the

letters and numerals is far more difficult. As originally made at the

factory (or prison, as the case may be), this second phase of painting

is usually accomplished by a machine which rolls the paint on in a

fashion that not only covers the top surface of the characters, but

extends it slightly over their edges, thereby achieving a much more

attractive appearance. The amateur restorer can generally hope to only

approximate the same result, and then only by using a hand roller or

laboriously painting the characters by hand. Either method requires a

steady hand, infinite patience and a willingness to fastidiously correct

any flaws that invariably result.

Below will be seen a sampling of restorations

gone bad. There are thousands of them out there, and these are but a few

of the mistakes to avoid. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| What’s wrong with this plate?

As a very important piece of history, this 1912 plate had quite nice

original paint when its unknowing owner repainted it to “make it look

better.” In doing so its value and aesthetic appeal were greatly

diminished, a fact that the owner, who later became a prominent license

plate collector, forever regretted. |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| Restored

|

|

Original |

|

| |

| 1916 Passenger. Seen here is a

common error in both amateur and professional restorations of 1916

plates, where the raised rim has been painted in the same silver color

as the numerals and letters. In fact, the rim is not painted on any New

Mexico plates through 1918, with the exception of the 1917 tags. |

| |

| |

|

|

.JPG) |

|

|

| |

Restored |

Restored |

Original, front |

Original, back |

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

1918 “thick” type Passenger.

The “thick” variety 1918 plates have serial numbers that begin

somewhere in the 13000 to 14000 range, continue up to about

19000, and have original colors of dark navy blue—almost

black—numerals and letters on an olive background. Something on

the order of a thousand or more of the thick variety tags,

mostly in the 18000 serial number range, were left over at the

end of the 1918 registration year and were apparently discarded,

then found years later in badly rusted condition. Many dozens,

and probably hundreds of these rusty plates are in circulation

today, a great many of which have been “restored.” In these

restorations, grossly incorrect colors were used, to wit, baby

blue on light grey, rather than the correct colors of dark navy

on olive. Moreover, in the restorations the raised rim was

painted in the same baby blue as was used on the raised

characters, even though the rim is not painted on

originals of either the thin or the thick varieties.

At left, above, are two examples of these incorrectly restored

plates, and at right can be seen the front and back of a couple

of original plates. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

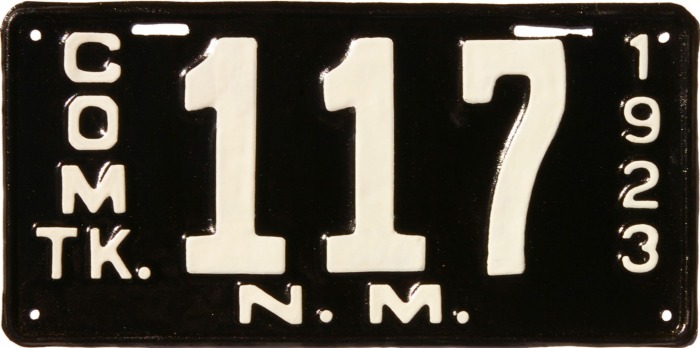

| Restored

|

|

Original |

|

| 1923 Commercial Car. Aside from

the metal being lumpy, bumpy and pitted, it has been repainted in

entirely the wrong colors. The chosen colors are those of a 1923

Commercial Truck plate, and the owner, who had an original example of

the latter, falsely assumed that the Commercial Car had to be the same

colors. That it is not can be seen from the photo of the original plate

at right, above. |

|

|

|

|

|

| Restored

|

|

Original

Colors |

|

| |

|

1923 Commercial Truck. Where someone got the idea that

1923 Commercial Truck plates are white on black is unknown, but there

are many of them in circulation painted this way. The paint on the plate

at right is not original, but at least is in the correct colors. But

even it is an example of a plate that was found with original paint and

never should have been repainted in the first place. |

|

|

|

|

| Restored

|

|

Original |

|

|

|

1925 Passenger Car.

Yet another plate “restored” in the reverse colors of what it should

be. This one is particularly puzzling because there are many surviving

1925 plates with good original paint, and nothing with which to confuse

the restorer except the 1925 Highway Department tag, of which there is

only one original example known (see below).

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

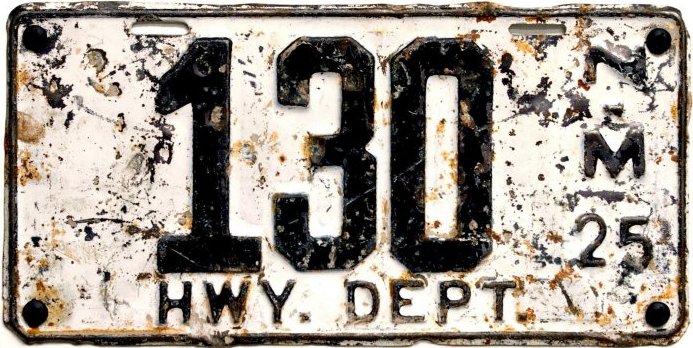

| Restored

|

|

Original |

|

| 1925 Highway Department. Here

is an example of a plate that someone assumed had to be in Passenger Car

colors. The fact that it is not is demonstrated by the original plate at

right, which is in the reverse colors. The restorer in this case could

perhaps be forgiven, in view of the fact that plate #130 above is the

only one known to survive with its original paint. |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Restored

|

|

Original |

|

| 1926 Commercial Truck. Again we

have an example of a plate that an amateur restorer assumed was in

Passenger Car colors, but is not. Compare it to the original plate at

right |

| |

| |

|

|

|

| Restored

|

|

Original |

|

| 1928 Commercial Truck. Another

example of a Commercial plate repainted in Passenger Car colors, whereas

the original plates are the reverse of those colors. |

|

|

| |

| Here we have a matched pair of 1938

Truck plates with a pretty good repaint. So what's not to like?

They're repainted in the wrong colors, matching those of Passenger Car

plates for this year. At right, for comparison, is a 1938 Truck with

original paint, these being in the reverse colors of 1938 Passenger Car

plates. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| 1948 Truck plate repainted in

the wrong colors, matching those of Passenger Car plates for this year.

At right, for comparison, is a 1948 Truck with original paint, this

being in the reverse colors of 1948 Passenger Car plates. |

| |

| |

|

| |

| Varnished plates. Decades ago,

mostly during the 1950s and earlier, there was a misguided belief among

some collectors that license plates should not be preserved in their

original state, but should be “protected” by varnishing them (or as some

people would say today, by clear coating them). Doing so, however,

imparts a grossly unnatural appearance, almost if they were made of

glass. Worse yet, the varnish in many cases acts on the original paint

in much the same way as paint remover does. With the varnish applied,

the original paint softens, bubbles up, and breaks into little pieces

which float around until the varnish sets up. The photograph above

illustrates just such an example. The plate was a superb original 1944

passenger plate which was instantly and permanently ruined upon having

varnish applied to it. |

| |

| |

| |

| Photo credits: 1918 #18831 courtesy

Michael Breeding. |

| |